DOCUMENTS OF TIME: PHOTO ARCHIVE OF OLEKSANDR RANCHUKOV

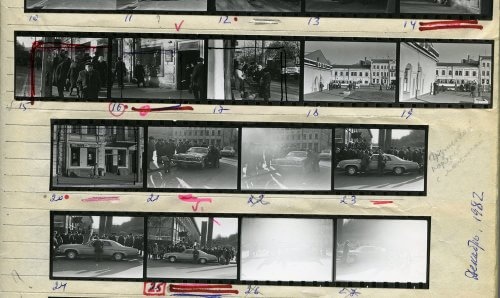

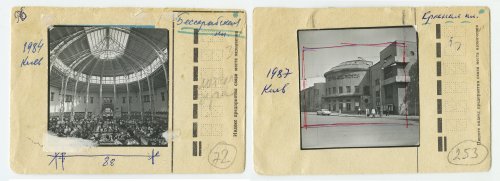

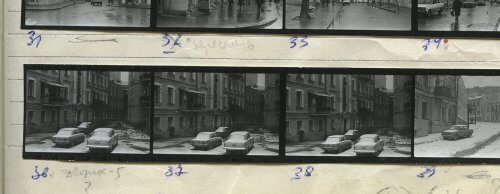

“Boarding the Tram”, “Meshochniki” (Bagmen), “Asking the Way”, “Brezhnev Died” — captions on the envelopes with negatives from the archive of Oleksandr Ranchukov (1943—2019). A separate envelope with a pasted on it control print for each negative of 6×6 cm format and cut into pieces of 4-6 frames of 35-millimeter films. In total — thousands of negatives from the 1970s to 2010s.

On April 2020 at the Laboratory of Contemporary Art — Mala Gallery of Mystetskyi Arsenal — should have taken place (scheduled before the quarantine) an official opening of the exhibition of photographs by Olexandr Ranchukov — the result of work with his archive, provided by the photographer’s daughter — Klavdia Demidova-Ranchukova.

On November 26 we finally open the exhibition “Archive of photographer Oleksandr Ranchukov”

The first impression from working with the archive is the joy of physical contact with envelopes, control prints, the “analogue” template of the Above the Roofs (2016) book with hand-glued photographs, and a pencil-graphed layout. Absolutely, such physicality is an important component of one’s perception of photography, especially photography of the “pre-digital” age. The consistency of the author’s work method and meticulousness of the archive structure immediately becomes clear — each envelope is carefully signed in the format “date, place, description”. However, no doubt it is not the main value of Ranchukov’s oeuvre.

What, where, and when — this is the main immanent form of recording information about a photographic image, starting with the first known photographs. This versatile format of image titling also captures the creator’s intention. In fact, it is a genome of photography, especially of that kind of it, which is commonly called “documentary.”

Courtesy of Klavdia Demidova-Ranchukova.

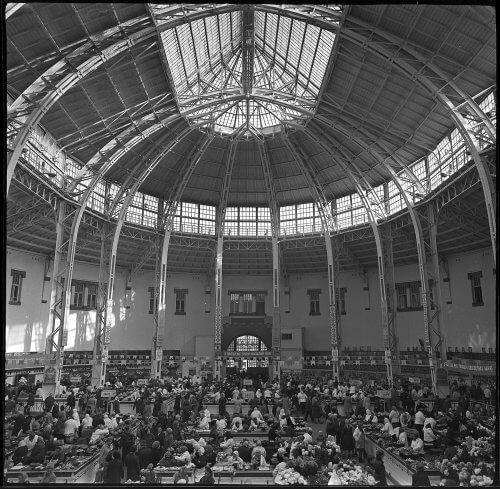

Ranchukov’s photographs were interpreted very differently depending on the publication’s purpose and the presentation context. Published in the Kiev, 70s-80s. Photo Album (2010) [1], his photographs become an instrument of nostalgia, illustrations of Kyiv’s past. The foreword to the album reads: “… a photo essay on the Kyiv everyday life in the times of the fading socialsim epoch, which is also sentimentally sad, a farewell look at the city of those years filled with a slight irony, the image of which [the city], at one time being familiarly mundane, now seems nostalgically beautiful to many of us” (by A. Voznitsky).

The impression from these photographs is quite different in the Oleksandr Ranchukov. Those Were the Times (2008) [2] book, which included photos from the Soviet Lifestyle series. This collection created a more critical narrative and included more photographs depicting people and the city under challenging circumstances, in times of dramatic change. Here, the same images are perceived as a material for a much more critical analysis of “those times,” almost as documents for criminal proceedings, though not lacking the same feeling of nostalgia for the recent past.

Much of the photography in both publications was taken in 1982-1983. It was 1982 when Ranchukov began to feel acute about the end of the existing political system and inevitable social changes. He stopped using a bulky medium format, preferring a more mobile 35 mm camera instead and begins to record the collapse of the system on a daily basis — as a document for the next generations. He deliberately works “for the desk drawer,” creating evidence for the future society, and which he doesn’t plan to show or publish immediately.

Displaying photographs in a gallery that works with art projects apparently would imply that these photographs must be artistic. However, Ranchukov did not consider himself an artist, and therefore, neither his photographs — art. According to the author, they couldn’t be considered as art, because they weren’t manipulated or constructed — a contradictory thought that reveals the everlasting question about the “artistic value” of documentary photography. Indeed, Ranchukov’s photographs are “documentary” in the classical sense of the term — there is no pre-arrangement; people do not pose. The author does not intervene.

Courtesy of Klavdia Demidova-Ranchukova.

Documentary photography should have been authentic, convey the essence of the depicted scene, and truthfully represent facts and events — but what kind of activities does Ranchukov record? In his photos we see cityscapes, buildings, people on the streets. This is an absolute routine: a certain moment portrayed is not important at all, and people — are unknown. What really matters is the all-encompassing sense of the ara that emerges slowly and quietly. Ranchukov’s own life becomes his material. He depicts the immediate surroundings, telling the story, first of all, about himself, his time, his city, in his language.

People in Ranchukov’s photographs are not identified and strange (as in the photos of Diane Arbus) [3]; they are ordinary, almost familiar. But the everydayness of the scenes becomes surreal the more we look at these photos, one by one. The unhurriedness, resemblance, and emphasized normality/ordinance of the actors and situations, such as participation in a regular demonstration or boarding a tram, gradually create the impression that we are looking at a well-directed play, in which almost nothing betrays its synthetic nature and finality.

“Documentary” and “fine art” are the two polar characteristics of photographic practice that explain not even the result but the intention of its implementation. While reviewing Ranchukov’s archive, one question arises all the time: to which of the established categories should these works be attributed? Unwittingly, the analogy with the photographer Eugène Atget [4] comes up in mind, who called his studio and his works “Documents pour artistes”, declaring only a modest ambition to create images for tother artists to use as a source material. However, later numerous institutions, such as museums or libraries, have been purchasing his photographs and commissioning photo sessions. Yet, it was only after his death that Atget’s oeuvre was truly accepted and recognized as fine art. This was primarily due to the efforts of an American photographer Berenice Abbott, who persistently promoted his archive and introduced Atget’s name to the artistic context of New York in the 1930s. After publishing several books, she eventually sold the archive to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1968.

Eugène Atget, in his own words, “photographed all of old Paris” during its modernization, working daily for almost 50 years. Consistently and methodically, Ranchukov had been photographing Kyiv day after day for several decades, carefully collecting his material. The material that now serves as a document of time and place also became a “document for art.” The elapsed time affects the perception and value of photographs that we see now. It is inherent in the photographic medium “added value.”

Courtesy of Klavdia Demidova-Ranchukova.

In most Ranchukov’s photographs can be traced almost scientific, pedantic style of architectural photography — the main professional activity of the photographer. Visual analogies can also be found with the practices of the “Düsseldorf School” [5] representatives, especially with photographs by Thomas Struth [6]. However, unlike Struth, Ranchukov does not make typologies, does not make a general study of the topic. He also works with the fabric of the city, with the street as a reflection of the history of the place, its subconsciousness and the socio-cultural processes that lasted before. Yet, Ranchukov’s viewpoint is not estranged or focused on the entirety. Nor is it a close-up view to tell about a particular individual. The middle ground plans of Ranchukov’s camera do not intervene in the private space; there’s no conflict or direct contact with the subject. The composition is never accidental, but always carefully thought and balanced. His photographs are very pleasant to look at, probably the same as they were to the author at the time of their shooting.

Courtesy of Klavdia Demidova-Ranchukova.

The project with the working title 1982 aims to interpret and explore the Oleksandr Ranchukov’s photography in the artistic context, to emphasis the need for research and preservation of photographic archives in Ukraine. We hope to present this project at Mala Gallery soon after the quarantine will end.

1 [usually written] work which is meant to be rescued and revealed years or decades later when the political climate changes.

[1] – Ranchukov, A., Yakovlev, V., & Voznitsky, A. (2010). Kiev, 70s-80s. Photo Album. V. Nevzorov (Ed.). Kyiv: Sky Horse. ISBN: 978-611-7004-04-9

[2] – Oleksandr Ranchukov. Those Were the Times. (2008). Album from the “Ukrainian Photography” series. Artbook Publishing House. ISBN: 978-966-96916-8-2

[3] – Diane Arbus (1923-1971), an American photographer, one of the main figures in 20th-century art photography. Participated in the breakthrough exhibition New Documents at MoMA, 1967.

[4] – Eugène Atget (1857-1927), a French photographer known for his photographs of Paris at the turn of the XIX-XX centuries. It is believed, that Atget has had a huge impact on the further development of photography.

[5] – Dusseldorf School is a nominal title of a group of artists from the class of Bernd and Hiller Becher at the Dusseldorf Academy of Arts, which influenced the development of contemporary conceptual photography.

[6] – Thomas Struth (b. 1954), a German photographer, representative of the Dusseldorf School.